Israel’s Paradox of Authority (the paper)

Here’s the latest draft of my paper on the Israeli constitutionalism conundrum. It’s still a work in progress: I welcome feedback.

The presentation may serve as a friendlier introduction to my main arguments and findings. It also includes a detailed discussion of developments in law and government. Although my presentation took place well before October 2023, the discussion casts light on the structural deficiencies that have contributed to recent developments — and that had similarly contributed to the 1973 war, as one can easily see from the post-1973 Agrant National Inquiry Commission Report. The Agranat Commission wrote hundreds of pages on the informal nature of the Israeli army, and noted the glaring deficiencies in army and cabinet-army hierarchy of command. Israel has never defined a commander-in-chief.

A few points of interest that emerge from the discussion:

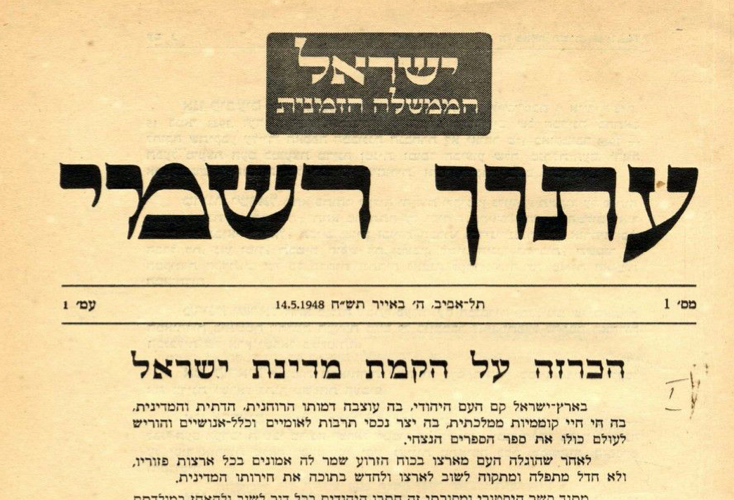

- Israel’s post-1949 law (that of the Unofficial/”official”/Reshumot) does not include an enacting clause. This matters for two reasons: (1) it is a problem in itself; (2) it is indicative of a problem. Here’s a way to get a sense why such a technicality is important. Imagine you receive a check that does not include the drawer’s information, i.e., that does not specify the author who has issued the order and bank account where the funds are to be drawn. Will you be willing to receive this check? Will you try to deposit it? Is it a check, and what is its value? (If you harbor doubts a check is a meaningful way for thinking about the law, I suggest you should consult Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech.)

One could think of post-1949 Israel as the place where no-drawer-checks are used as currency: one never deposits the checks, only endorses them further. This strange arrangement seems to work but sometimes comes under strain: (1) when 1948, i.e., pre-February-1949 (of the Official Gazette) checks come into the market, and their relative value must be ascertained; (2) when increasingly pompous checks are produced to distract from them having no cover. The result is (1) inflation, (2) a search for value elsewhere. - I offer an interpretation of and practical application for L.H.A. Hart’s Rule of Recognition. I separate between a Weak Hart Test of personal recognition in private: the child recognizes the mother’s voice; and a Strong Hart Test of personal recognition in public: the child distinguishes her mother’s voice amid the cacophony on the street. Israel’s post-1949 law (Unofficial or “official” Israel) passes the Weak but not the Strong Hart Test.

* To clarify: I do not quite follow Hart’s framework but rather adjust my own to accommodate, somewhat loosely, Hart’s concept. I can show in an elaborate discussion how, with some changes, both frameworks mostly agree but this would hardly be informative and useful here. A more rigorous discussion will separate between Recognition and Acknowledgement. - An important consequence follows the Israeli authority conundrum: all post-1949 state actions, regardless how minor, are relatively private and therefore necessarily aggressive. Why? Imagine the following scenario: it is the first day of school, and into the classroom enters a person, stands by the podium in front of the students, and begins to teach. What happens here? In our little scenario, authority is established outside the classroom, but legitimacy is evaluated inside. Let’s break it down:

(1) The person is the Teacher, acting with authority, when ordered (say, by the headmaster) to enter the classroom. The office, official status, is top-down, or outside-the-classroom.

(2) that person has (popular) legitimacy, if perceived by the students as acting with authority. The expectations of status are formed inside the classroom, bottom-up.

Normally, the first thing upon meeting the new class, the (presumed) teacher would substantiate her authority: “I am the teacher.” (It is that simple.) But what if the “teacher” has failed to introduce herself professionally (i.e., stating the public office?) and thus has not yet established herself as the teacher, without quotation marks? Or, what if one student has arrived late — as I usually do — only to have missed the introduction? Either way, authority is presumed and not substantiated (compare: discussion of presumption in Babylonian Talmud, Bava Batra, from chapter 3).

Now, the “teacher” approaches a student with a question, however immaterial, but within general classroom expectations. The evaluation of that simple act depends on the teacher’s authority (top-down: is that “teacher” really the Teacher?) and legitimacy (bottom-up: classroom’s perception). If a student follows a Strong Hart Test, expecting the “teacher” to introduce herself in official capacity as the Teacher in order to be considered as the teacher (presumption, authority, legitimacy), then the teacher is acting in personal capacity and her actions, however immaterial, could be reasonably deemed aggressive.

We can generalize the model by considering the possible scenarios to emerge from the variables: the “teacher” (presumption), the teacher (legitimacy) and the Teacher (authority, official status).

My account here is in fact so elementary that, according to Hollywood, it is the first thing we are exposed to: as in scenes where the mother/father (to make the point more pronounced, sometimes it is the adoptive parents) introduces themselves to the newborn by stating their relative authority, “I am your Mother/Father.”