Review of A Little Life by Hanya Yanagihara

No Rose Without a Thorn

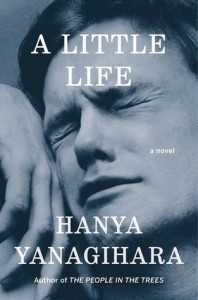

A NOVEL about the “little life” of a handsome, brilliant, successful New Yorker who says “I don’t think happiness is for me” and cuts himself regularly was bound to attract attention. Hanya Yanagihara’s second novel, A Little Life, was a bestseller and was shortlisted for the 2015 Man Booker Prize and the National Book Award. Critics, however, were sharply divided. A few extolled the emotionally demanding narrative–forget about a happy ending!–while others dismissed it as a manipulative attempt to impress readers solely by foiling their narrative expectations.

One expectation is that the handsome New Yorker, Jude St. Francis, will eventually come to his senses and stop hurting himself. The novel follows Jude from his twenties to age 53: he succeeds fantastically as a chief litigator for a private law firm, but his personal growth is stunted. While at law school he also took a master’s degree in pure math at M.I.T. and worked in a local bakery; he clerked for a Scalia-like justice whom he won over by singing a Mahler lied at the job interview; he gets up early every morning and swims before slaving at the office and coming home to cook.

Jude was raised not by a “tiger mother” but by Brother Luke, who abducted Jude from a monastery in South Dakota that had adopted the orphan after he was found in a dumpster near a local drugstore. In motel rooms across the country, the brother taught him piano, math, French, and German during the day and had his way with him at night. Running away from the monastery in his early teens only leads to more abuse and prostitution, a cycle that ends only when Jude enrolls in college–apparently Harvard–at age sixteen. (Yanagihara, fond of bestowing Ivy credentials on her characters, does not name the college for whatever reason.)

Until it takes on a gothic turn, the novel feels a bit like Friends or Seinfeld. Jude and his three former college roommates–Willem, an actor; JB, an artist; and Malcolm, an architect-settle in the big city after grad school. Yanagihara is at her most entertaining when she wears the anthropologist’s hat and unveils the workings of the New York ethos of ambition and professionalism. (Her first novel, 2013’s The Men in the Trees, based on a true story, features an anthropologist who molests children of the Micronesian tribe he explores.) The four return to their regular Chinese restaurant despite its food. They put up with boring jobs on the way to a great career (the Whitney will host JB’s retrospective before the book ends). Best friends Jude and Willem sublet a cheap one-bedroom in downtown Manhattan, where every year they host an overcrowded New Year’s Eve party. Fast forward a little over ten years, and all have smoothly graduated to the top one percent of their professions and begun to spend their free time on decorating fancy lofts in SoHo and houses upstate.

Beside the college friends, two other supporting roles complete Jude’s social circle. His Harvard law professor, Harold, is a mentor and friend who formally adopts the thirty-plus Jude and thus becomes literature’s first Jewish parent to respect his son’s privacy. Jude gets the family he never had but still can’t believe he’s loved. His doctor Andy is always available to treat his legs, which are subject to an increasingly complicated disability. Jude is loyal to his friends but is easily annoyed when they start asking questions. Amazingly, they, the doctor, and the adoptive father all learn about his self-cutting behavior and in effect condone it. This heedlessness can perhaps be explained by a comment Yanagihara made (to ElectricLit.com) where she said that male friendship is “built upon a mutual desire to not truly know too much.” She said she was interested in exploring male feelings, given that men “are equipped with a far more limited emotional toolbox [than women].” Women, in fact, with the exception of a lesbian social worker, are conspicuously absent from the narrative.

Intriguingly, Yanagihara uses gay men to maintain and purify her male focus. A Little Life deserves a mention in any anthology of gay literature, at the very least, for its unconventional treatment of gay identity. There are so many gay characters–including Andy’s brother and various random people–that it seems gay is the new normal. Jude’s sexuality is part of the protagonist’s mystery. “Jude’s sex life, his sexuality, had been a subject of ongoing fascination for everyone who knew him,” writes Yanagihara. In a reversal of the pattern of men who lust for other men but are too timid to act on it, Jude doesn’t know whether he’s physically attracted to males but regards relationships with men as his default position, with sex an obligation that he detests.

When a fashion executive hits on the forty-something Jude, he’s reminded that he’s lonely and enters his first adult sexual relationship. Yanagihara seems bent on suggesting that a man is ever trapped by his past: it’s obvious early on that Caleb, the executive, is abusive and he will beat and rape Jude. A suicide attempt is followed by a short-lived tentative happiness as hitherto straight Willem suddenly discovers an attraction to his best friend, and they become a couple.

Garth Greenwell, writing in The Atlantic, suggested that “queer suffering is at the heart” of the novel. Jude’s secretive past, feeling of otherness, reliance on friends, the absence of family, and self-hatred evoke the gay experience of a time long before the “It gets better” campaign. Stylistically, too, the melodrama and over-the-topness are markers of gay aestheticism. Writes Greenwell: “The book reminds readers of the long filiation between gay art and the freakish, the abnormal, the extreme–those aspects of queer culture we’ve been encouraged to forget in an era that’s increasingly embracing gay marriage and homonormativity.”

But here’s a different interpretation: Yanagihara has written a liberal fantasy. Although gays are everywhere, their gayness is unimportant. “Gay” is little more than a label of a sexual attraction with not much psychological importance. Take Malcolm, who hastily comes out as gay only to recant and marry a woman. Yanagihara likewise questions the reality of race and ethnicity. Malcolm, again: born into an interracial family, he’s as indecisive about his race as about his sexuality.

Yanagihara obviously delights in defying expectations. Her nonchalance can be charming–gays for whom gayness is not a burden; a black man (JB) strategically using his race to excel in the final project in college; a white man (Willem) “admitted [to college] as a sort of unofficial poor-white-ruraldweller-oddity -affirmative-action representative”; and Jude, dubbed “the post-man” because it’s impossible to tell his ethnicity or sexuality. Yanagihara captures the New York ideal that talent, hard work, and a top school determine success.

But this nonchalance comes at a cost, because it’s not psychologically true-to-life. For example, when Willem realizes he’s attracted to Jude, “[i]t was beginning to worry him. Not because Jude was a man: he’d had sex with men before, everybody he knew had.” That’s witty but glib. Here and elsewhere, Yanagihara engages in what might be called a “deus sex machina” in which men’s sexuality can be conveniently twisted and turned. And if sex between men in A Little Life is so far off the mark, how likely is it that Yanagihara will arrive at a realistic understanding of men’s emotional toolbox?